Above, cast of The Black Rider (photo by Clayton Jevne)

Well, it is not your typical Christmas Holiday fare, but you could do a lot worse than take yourself to see Theatre Inconnu’s production of Tom Waits’ and William Burroughs’ 1993 musical The Black Rider. The plot is based on an early 1800s German folktale titled The Fatal Marksman, a familiar twist on the sell-your-soul-to-the-Devil trope so popular in literature and art. Young Kathchen (Melissa Blank) has fallen for a clerk, Wilhelm (Nicholas Guerreiro), but father Bertram (Cam Culham) insists that his son-in-law be a hunter, so Wilhelm falls into the clutches of Pegleg (Rosemary Jeffery) who provides him with magic bullets that lead to his success at winning Kathchen as his bride. But the twist in the tale leads to inevitable tragedy.

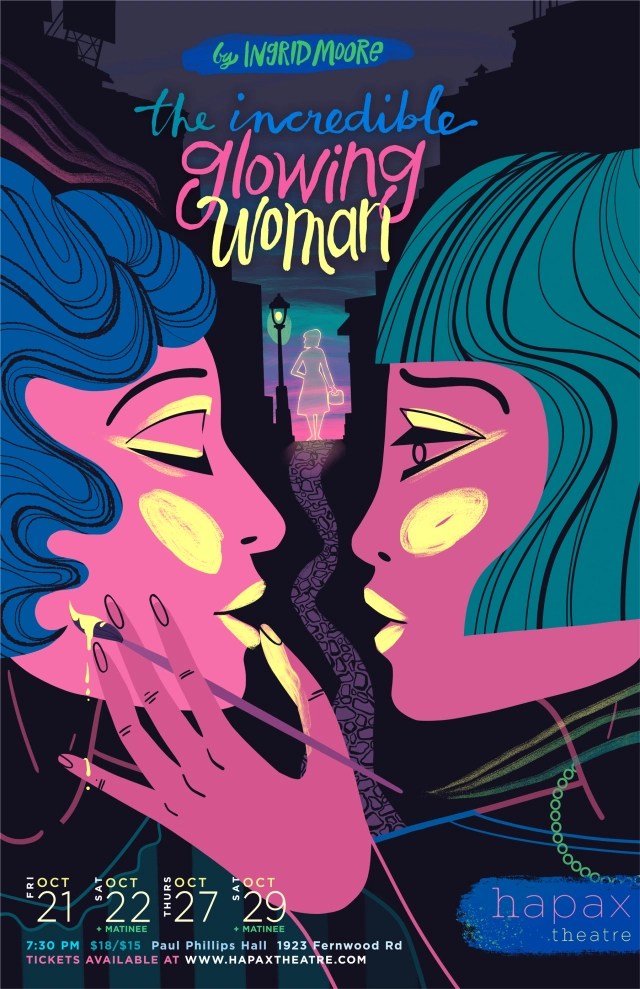

All of this is supported by Waits’ songs and Burroughs’ poetic text, written in rhyming couplets. The music features a couple of memorable tunes, “The Briar and the Rose” and “I’ll Shoot the Moon” are two that stuck in my head after the show. Director Clayton Jevne has cast the show very well, and as usual makes the most of the small stage in Paul Phillips Hall. Here, he’s supported by movement coach Sylvia Hosie, who creates some good effects with simple gestural motions rather than full-on dance. The set, designed by Jevne, works well, with shimmery translucent legs on each side of the stage, and a shadow theatre in the rear that is used effectively in multiple ways throughout. The costumes by Linda MacNaughton work well, capturing the early 1800s period.

While everyone in this nine-person cast has a standout moment or two, I want to highlight three actors who really impress. First is Nicholas Guerreiro, who shines in his role as Wilhelm, capturing well the manic intensity of a man who has given himself over to the dark side. Guerreiro is all arms and legs and makes the most of his lanky physicality in the role. Next is Ian Case, who plays multiple roles including Wilhelm’s uncle, the Duke’s messenger, and my favourite, William Burroughs himself. Case is an excellent actor, and he nails each of these characters with economy and precision. Finally, I was blown away by Rosemary Jeffery’s portrayal of Pegleg. She plays the part with great gusto, cackling with delight as all of her nefarious plans fall into place. The company all wear German Expressionist style pale face makeup, which heightens the theatricality throughout.

My one regret about this excellent show is that it lacks live music. While Brooke Maxwell has created an effective soundtrack (although not nearly as edgy as Waits’ original recording), I did miss seeing a live band perform. That said, this is an excellent production, and one you only have until next weekend to catch. Highly recommended. Tickets are available online at theatreinconnu.com.

Ian Case as William Burroughs (photo by Clayton Jevne)

Nicholas Guerreiro as Wilhelm and Rosemary Jeffery as Pegleg (photo by Clayton Jevne)